At first glance, Wi-Fi deployment often looks deceptively simple. You choose a router, place it somewhere “reasonable,” connect it, and expect wireless connectivity to just work. For small spaces and light usage, this approach sometimes appears sufficient — until real-world conditions expose its limitations.

In practice, Wi-Fi deployment is not a universal checklist but a context-dependent process. The same technical steps — access point placement, channel selection, power levels, and security configuration — lead to very different results depending on where and how the network is used. An apartment, an office, a hotel, and a high-density event all impose distinct physical, behavioral, and operational constraints. Ignoring these differences is one of the main reasons Wi-Fi networks degrade over time, even when the hardware itself is technically capable.

Understanding these contextual differences is the foundation of a reliable deployment.

Wi-Fi Deployment in Apartments and Residential Buildings

The same phrase “WiFi deployment” signifies very different risks and priorities depending on the intended use of the space.

In a residential building, the main challenges are often trivial: geometry, materials, and “where to place nodes to avoid dead zones,” plus the tradeoffs of mesh networking. Home mesh systems are often built around the idea of ”covering zones,” but the architecture and node placement themselves are critical because each node creates a separate service area and depends on the quality of the backhaul.

What is often overlooked is that a poorly placed mesh node does not just fail to improve coverage, but can actively reduce overall network performance. A weak or noisy backhaul link forces the node to retransmit data, consumes shared airtime, and increases latency for all connected devices. In practice, this is one of the most common design mistakes in residential Wi-Fi networks, especially when placement decisions are made without understanding how mesh backhaul actually behaves in real environments.

This problem is amplified by building materials. Concrete, brick, metal-reinforced drywall, and floor slabs between levels often degrade inter-node backhaul links more severely than client connections, particularly when the same radio band is used both for client access and node-to-node communication. As a result, effective mesh design is less about adding more nodes and more about ensuring clean, high-quality backhaul paths, appropriate inter-node distances, and conscious use of frequency bands — a point frequently highlighted in discussions of common Wi-Fi network design pitfalls and how to avoid them.

Wi-Fi analyzer and survey applications are especially useful here, even for home users. Without relying on guesswork, these tools make it possible to observe signal quality, noise levels, roaming behavior, and channel usage in real time, helping to verify whether a mesh node actually strengthens the network or silently drags it down. This shifts mesh deployment away from the simplistic “more coverage equals better Wi-Fi” mindset toward deliberate, measurement-driven design.

Wi-Fi Deployment in Offices and Workspaces

In an office, even a small one, other constraints quickly arise: high device density (BYOD), commuter traffic, meeting rooms as “peak points,” and requirements for stable roaming and predictable capacity. It’s easy to make a mistake here if you only focus on “getting a good signal,” ignoring airtime, co-channel interference, and the actual network load.

Office Wi-Fi fails most often during moments of collective activity — meetings, video calls, shared presentations — not during idle hours. This is where the difference between coverage and capacity becomes obvious. A signal can be strong, yet the network becomes unusable because too many devices compete for the same airtime.

Successful office deployments prioritize controlled channel reuse, reasonable channel widths, and consistent roaming behavior over raw signal strength. Without this, even modern hardware struggles under real workloads.

There is another often-overlooked factor in office Wi-Fi design: the weakest or oldest device on the network.

In many offices, there are devices that cannot be replaced easily — legacy laptops, barcode scanners, printers, VoIP handsets, industrial controllers, or specialized equipment tied to business workflows. These devices may support only older Wi-Fi standards, narrower channel widths, or lower modulation rates.

Even if such devices generate little traffic, they still participate in the same shared medium. Wi-Fi is not a switched network — airtime is shared. When a slow or legacy client transmits, it occupies the channel for longer periods, effectively reducing the available airtime for everyone else. As a result, a single outdated but essential device can become a silent bottleneck during peak usage.

This is why office Wi-Fi design must account not only for how many devices connect, but also which devices must be supported. Sometimes this leads to deliberate design compromises: separating legacy devices into dedicated SSIDs or bands, limiting channel width, or favoring stability over maximum theoretical throughput. Ignoring these constraints often produces networks that benchmark well in isolation but fail under real operational conditions.

Wi-Fi Deployment in Hotels and Hospitality Environments

In a hotel, the specifics of a guest network are compounded: segmentation (guest vs. staff vs. services), customer isolation, different zones (rooms/lobby/backrooms), and complex building physics (thick walls, corridors, multiple rooms). Therefore, hotel deployments almost always require more stringent design discipline and security/segmentation policies.

Hospitality environments combine the physical challenges of residential buildings with the operational demands of enterprise networks. Long corridors, repeating room layouts, and dense construction materials distort signal propagation in ways that are hard to predict intuitively.

At the same time, guest isolation and security policies are non-negotiable. A hotel Wi-Fi network is not just about connectivity — it is part of the guest experience. This is why hotel deployments rely heavily on careful access point placement, conservative channel planning, and post-deployment validation.

Wi-Fi Deployment at Events and High-Density Venues

And in an event/high-density environment, the main challenge isn’t “killing the signal,” but rather supporting the simultaneous activity of hundreds/thousands of devices without drowning in interference. There, the principles of maximum channel reuse, careful channel width, and physical separation of coverage “cells” come into play, because simply “adding APs” doesn’t provide a linear increase in capacity.

High-density Wi-Fi behaves fundamentally differently from home or office networks. Airtime becomes the scarce resource, not signal. Poorly planned deployments often collapse precisely because additional access points increase contention instead of capacity.

This is why event Wi-Fi design focuses on shrinking cells, narrowing channels, and deliberately controlling where clients associate — concepts that are well documented in professional RF design literature.

In practice, this usually includes limiting the number of SSIDs to reduce management overhead, disabling the lowest legacy data rates so clients do not occupy the channel longer than necessary, steering capable devices to 5 GHz and 6 GHz bands, and sometimes reserving 2.4 GHz only for specific, low-throughput use cases.

Directional antennas and carefully planned AP mounting help confine cells to defined seating or standing areas instead of “bleeding” across the entire venue. On top of that, capacity planning has to assume upload-heavy traffic patterns (photo and video sharing, live streaming), not just downstream usage, so both RF and wired backhaul must be dimensioned with uplink behavior in mind.

Why analysis and planning tools matter

Because Wi-Fi behavior changes so dramatically across environments, configuration by intuition rarely works. This is where analysis and planning tools become essential.

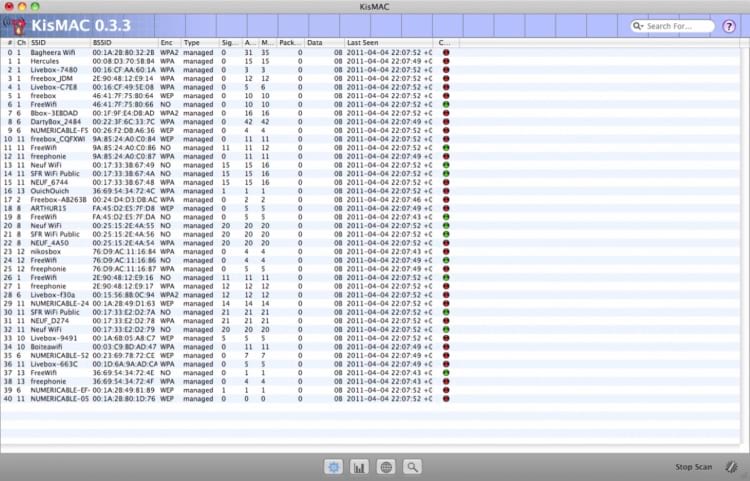

Tools like KisMAC help at the early stage by revealing the surrounding RF environment and showing what is already happening in the air. This alone prevents blind channel selection and accidental interference.

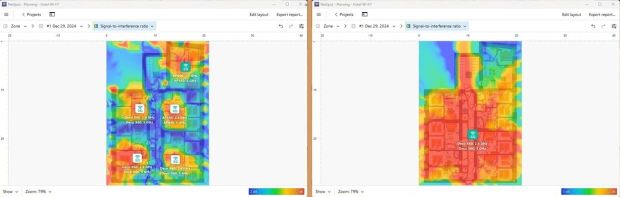

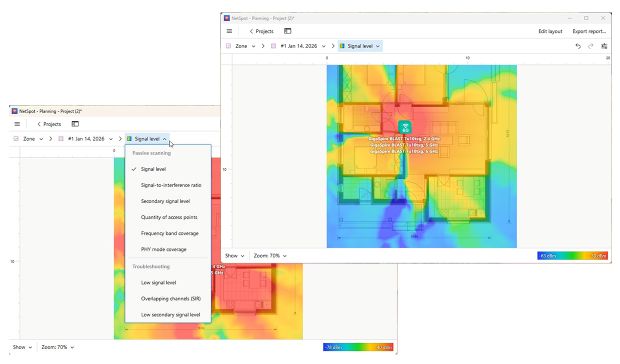

More advanced tools, like NetSpot, go further by combining inspection, on-site measurement, and predictive planning.

They allow you to connect physical space, RF behavior, and expected load into a single model, making deployment decisions measurable instead of speculative.